cross-posted from: https://slrpnk.net/post/7419366

TLDR: New REBCO superconductor can operate with significantly less insulation, allowing them to be built much smaller. Thereby making critical space for other components.

From the article:

“The standard way to build these magnets is you would wind the conductor and you have insulation between the windings, and you need insulation to deal with the high voltages that are generated during off-normal events such as a shutdown.” Eliminating the layers of insulation, he says, “has the advantage of being a low-voltage system. It greatly simplifies the fabrication processes and schedule.” It also leaves more room for other elements, such as more cooling or more structure for strength.

How compact are we talking? 3 story building or Mr. Fusion?

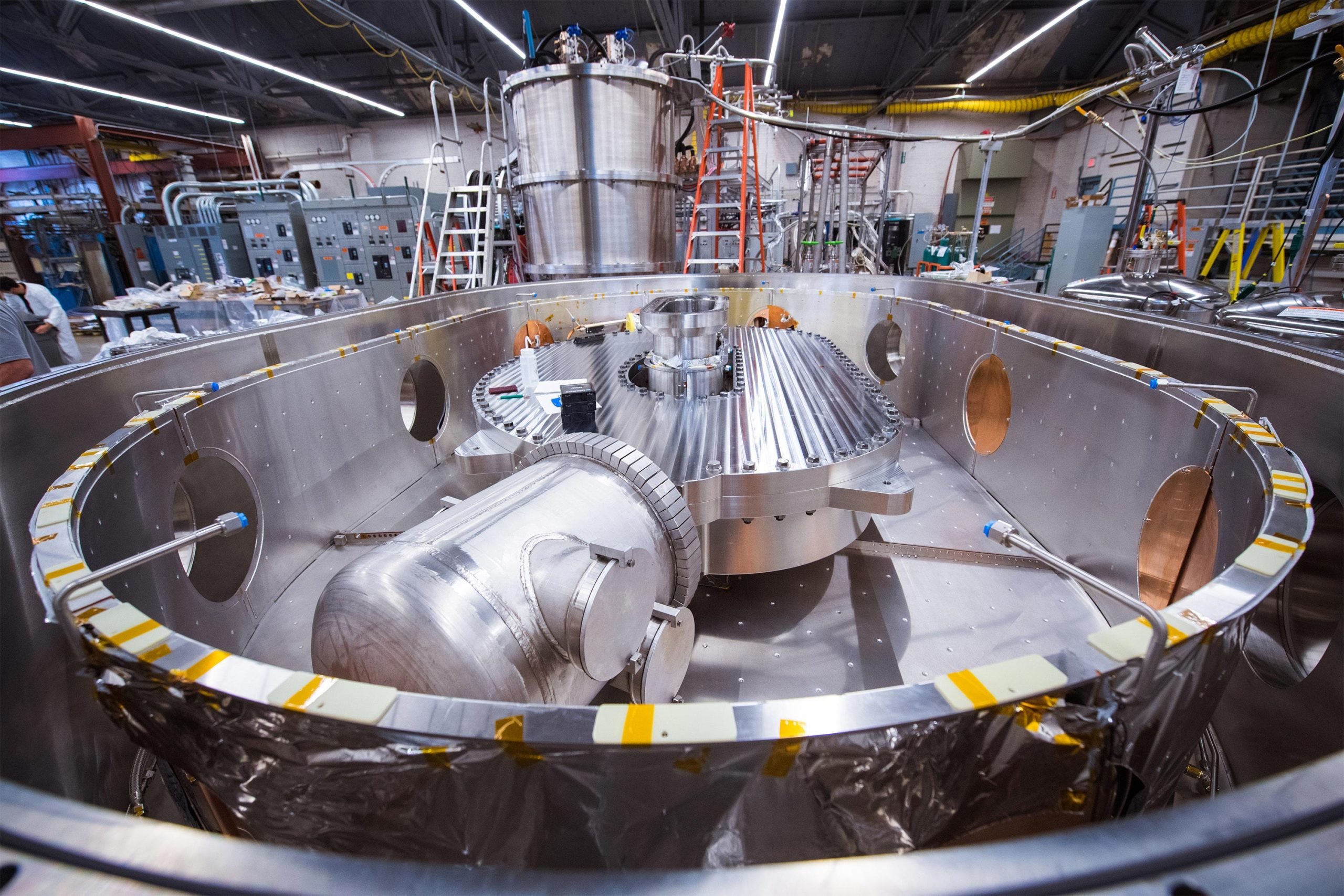

Not Mr. Fusion, but a modest industrial facility that could fit in an industrial park rather than the very large ITER which has its own complex. The ARC reactor design from commonwealth fusion is expected to have a major radius of 3.3m whereas ITER has a major radius of 6.2m. That might not sound like a big difference, but material costs and supporting systems cost roughly scale with volume which is a factor of 8 difference.

https://youtu.be/fKREB8IvCbs?t=25m33s

Here’s an old, but good talk on the motivation for this proof of concept. I linked the most relevant time, but the entire presentation is worth watching if you find it interesting.

Personally, I find this success to be way more exciting than the NIF breakeven shots. Those were neat milestones, but don’t get us closer to a feasible commercial design. This REBCO magnet demonstration makes commercial fusion a possibility in a timescale that could matter.

At scale? Or just the one?

Looks like we’ve been making this stuff since 2006 and at decent enough volumes since then.

About 10 km of REBCO was delivered by SuperPower that year in the world’s first manufacturing demonstration to construct a 30 m long power transmission cable that was installed in the power grid

Did someone find the info, what “high-temperature” actually means? I must have missed that part in the article. Thanks in advance :)

20 Kelvin, which still requires substantial cryogenic cooling systems but is much easier to maintain than 4 Kelvin liquid helium.